Interview by Matthew Raj Webb

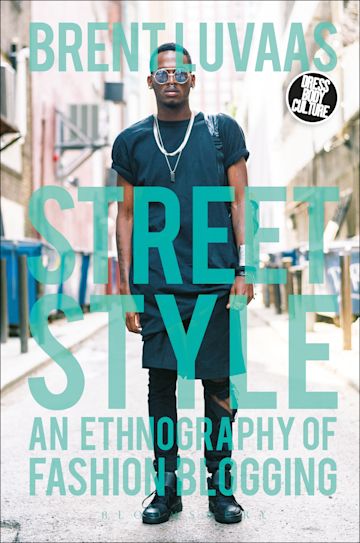

https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/street-style-9780857855756

Matthew Raj Webb: Not so long ago, fashion showed up in anthropologists’ writing largely as a pejorative. Today, fashion practices, media, and industries are at the center of many important and far-reaching theoretical debates. There are even dedicated graduate programs in so called “Fashion Anthropology.” What drew you to the topic, and what does your study of street style blogging reveal about fashion as a variegated social field?

Brent Luvaas: I’ve always been interested in fashion, how people present themselves to the world around them, and the stories people tell about themselves through the clothes they wear. As the kid dressed all in black in the corner of my high school cafeteria, fashion and its relationship with identity seemed like an obvious thing to study. Even my early ethnographic work on indie music in Indonesia was as much about what bands wear as the music they play. It was only when I became interested in bloggers, however, that I made the choice to make fashion an explicit focus of my anthropological practice. I learned a lot about fashion as a variegated social field from the project, both in terms of the ways people mix and match clothes in their everyday sartorial practice and, more importantly, in terms of how fashion, as an industry, has re-structured itself in alignment with digital technologies. Blogging wasn’t just an exception to the fashion industry as usual, a way outsiders and amateurs could get in on the game. It transformed the inherent logic of the industry. Now everyone in the fashion industry has to present, market, and brand themselves the way the bloggers did. Blogging may be out of fashion now, but the impact of blogging on the industry can’t be overstated.

Matthew Raj Webb: One of the main threads in your book concerns the tensions between global democratization of access—such as via the internet and digital cameras—and the remediation of professional/amateur distinctions, both in the field of fashion photography and within anthropology. Could you elaborate on your point of view here? From your perspective, how have new media of fashion—and anthropology—transformed or reinforced historical hierarchies of value?

Brent Luvaas: I think we have to distinguish between the methods through which hierarchies are established and performed and the hierarchies themselves. Fashion has always been about exclusivity. It’s built into its very concept. The industry depends on it, creating a model whereby the fashion elite continuously work to distinguish themselves from everyone else. When a trend reaches peak saturation, fashion moves on. Digital technologies like blogging and social media have not eliminated that elite. They have simply transformed the methods and tools people use to become that elite. There was an elite class of bloggers when I was doing my research. They have now rebranded themselves as social media influencers. Social media has become a critical part of becoming part of the fashion elite today. It is an industry requirement. We could argue that it has, to a certain limited extent, widened the scope of who can become that elite. There are today more people of color in the fashion industry than there used to be, having built a large enough following through social media to demand that the industry pay attention to them. There is also more body diversity. But the industry remains primarily skinny and white. It remains insular and exclusive. It is still a social field—like anthropology itself, I might add—where social, cultural, and economic capital are critical to achieving success.

Matthew Raj Webb: I was captivated by Chapter 5, where you discuss bloggers’ collaborations and partnerships with fashion businesses—brand associations that you actively pursued for your own (highly successful) style blog, Urban Fieldnotes. From the point of view of street style bloggers in the mid-2010s, what did the opportunities and constraints of cultural production within the commercialized field of fashion look like? How do you think these might have changed today?

Brent Luvaas: I’ve touched a bit on this in the previous questions, but perhaps a bit of blog history is important here. There was a moment, in about 2005-2007, when blogs, run through free platforms like WordPress and Blogger, were not a commercial enterprise—at least not for the bloggers. Street style bloggers got into the game because of an abiding interest or passion. They weren’t making money from them and most people I interviewed who had blogs at that time claim it hadn’t even occurred to them that they could make money from them. But after bloggers like Scott Schuman of The Sartorialist and Tommy Ton of Jak & Jil started shooting for magazines like GQ and Vogue and getting brand partnerships with American Apparel, Burberry, and others, a new generation of bloggers emerged with the explicit intent of using their blogs to enter into the industry. They were the predecessors of today’s fashion influencers. The game began to shift, and more and more bloggers began showing up outside the shows at Fashion Week hoping to either be noticed by the photographers or capture those up-and-comers who would help them build a name for themselves as photographers. Blogging, and later social media, became a key part of how people build careers in the fashion industry. The outsiders re-wrote the rules of the fashion industry. But then, fashion has long been an industry of outsiders. This might be more of a case of the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Matthew Raj Webb: Street Style cuts across locations like Philadelphia, New York, Boston, as well as Jakarta, Cape Town, and Athens, drawing on aspects of your auto-ethnography and para-ethnographic research. As a community of practice and cultural phenomenon the world of street style blogging is thus globally diffuse and diverse, but you nonetheless note that participants tend to share a middle-class position. How do these factors lead you to understand the value of the street as a representational idiom and context?

Brent Luvaas: As you stated in the question, street style bloggers tend to be middle class. If you want to get your work recognized, you need to be able to produce the aesthetics currently valued by the industry. To produce those aesthetics, you need expensive camera equipment. It was not unusual for bloggers I encountered to have spent upwards of $10,000 on their cameras and lenses alone. Plus, not everyone’s perspective on style gets the same amount of attention on social media. An ability to recognize and anticipate what the industry values in fashion is required, and that ability is not universally distributed. It remains the exclusive domain of a particular kind of urban, cosmopolitan, middle-class person. Despite a rhetoric of democratization, there was never an equal playing field in the street style game. Nonetheless, there is a diversity of perspective, particularly across regional and national boundaries. Street style bloggers actively sought to elucidate that diversity through their work. They highlighted their own city or nation’s distinct flavor and style. They sought to put their own city on the global fashion map, and in doing so, they practiced a form of amateur visual anthropology. Street style, then, is a global phenomenon with distinctly local characteristics. And it depends on a shared conception of the street —itself derived from western European models of urban design—as a public, highly visible space where people perform identities for others to see. Street style blogging has helped perpetuate and extend the reach of that concept. It has real, practical implications for how public spaces are conceptualized, accessed, and designed.

Matthew Raj Webb: Street Style was published in 2016, you have subsequently written about how deeply the project affected you (Luvaas 2019), stating that you remain in some ways haunted by the habitus you acquired. Could you please talk a little about what it has meant for you to leave the field given the ubiquity of fashion media and intimacy of dress politics in everyday life? Moreover, I’m curious to know your thoughts on what it feels like to age as a researcher—and human!—deeply immersed within the world of fashion?

Brent Luvaas: For those of us who do work in the digital realm in some capacity (and perhaps that is most of us these days), there is no “leaving the field.” Not really. Today, we remain linked, via Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and other platforms to the communities we study. We are (rightfully) held more accountable for what we have to say about our interlocutors. We have trouble gaining distance. That is doubly true for those of us who employ auto-ethnography as a key part of our practice. For us, we have made ourselves an explicit subject of our own work. I studied street style blogging by becoming a street style blogger. I picked up a camera, walked the streets, and learned to intuit cool the way a street style blogger does. I hung out with fashion people, got free-lance employment by the fashion industry, and became increasingly self-conscious about what I wore and when. All that messes with your head. All anthropologists are changed by the field in some way, but how do we live with these changes when we’re never really able to leave the field? I’m still wrestling with that question myself. What has become clear to me is that I need to consider before I start a new project who I will become by doing it. That is especially true as a middle-aged cis-gendered, heteronormative white guy. Some research options are off the table for me. I can no longer build a project around hanging out with twenty-something Indonesian hipsters until four in the morning every night. That would be creepy. People are not super likely to want to talk to me. I would also likely have a harder time building a following as a social media influencer than I did nine years back. Fashion has carved out greater space for people over 40 in recent years. But that space is limited, and my ability to access it even more limited. Rather than combat the youth cult of fashion and the psychological damage it could inflict on me, I’ve turned my attention to other practices of visuality, less tied to age. Lately, that has been street photography. I’ve learned a lot from street style blogging, but the biggest things I’ve gained are an appreciation for the camera as a tool of perception and an appreciation of the street as a space where culture is improvised and performed. I am taking that appreciation into my new work, moving away from the fashion industry, but still walking the same streets.

References

Luvaas, B. 2019. “Unbecoming: The Aftereffects of Autoethnography.” Ethnography, 20(2): 245–262.