https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9781501778810/politics-of-tranquility/#bookTabs=1

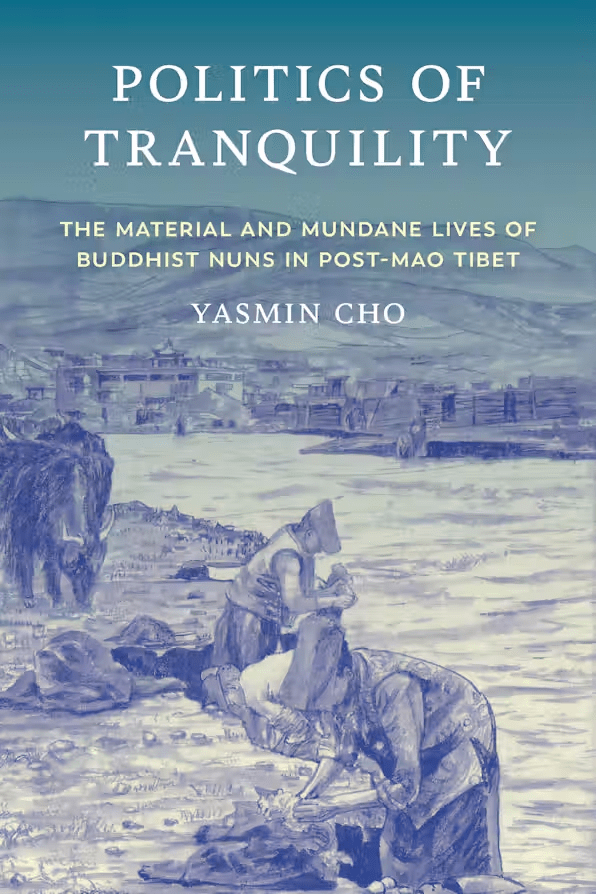

Isla: First, I would like to thank you for conducting this challenging fieldwork, writing stories of these nuns, and presenting us with an alternative way of living and expressing themselves as Tibetans beyond the binary assumption centered on rebellion and victimhood. This ethnography is an invaluable piece of documenting and reflecting on the everyday lives of Buddhist nuns in Tibet, whose access is constrained. Would you mind sharing how you started this research project? As a layperson, how does your Buddhist practice resonate with the research, vice versa?

Yasmin Cho: Thank you so much for inviting me to talk about my book. I first visited Yachen Gar in the summer following the first year of my PhD program in the United States. Though I had been fascinated by Tibet for years and was eager to explore the plateau, I hadn’t decided on a fieldwork site yet. Having heard Yachen mentioned almost in passing, I decided to visit to check it out. It soon became clear, because of the difficulty in getting there, that Yachen is not a place one simply checks out. The journey began in Chengdu and required bus transfers in Kangding and Ganzi; each leg of the journey took ten to twelve hours over roads plagued by recurrent construction and grueling traffic. From Ganzi, the final segment involved a dilapidated shuttle bus that ran once a day. This was the most treacherous stretch—a series of muddy, meandering mountain tracks navigated by a severely overloaded vehicle. A Tibetan friend from Ganzi once described the path to her hometown as “hell,” and I found myself in grim agreement. Perhaps it was this initial struggle that subconsciously steered my research toward the material engagements of religious practice. The physical toll and raw sensory experience of being in Yachen became a recurring theme during my time in the field. Upon arriving there, I expected the curated calm of a traditional monastery, but instead, I encountered a sprawling, chaotic shanty town; shabby, self-built huts stood dangerously back-to-back, forming a disorganized and unruly maze. While the presence of monastics, Buddhist statues, and prayer wheels confirmed its identity as a religious community, Yachen felt less like a formal Buddhist institution and more like an overcrowded village of 12,000 inhabitants, including over 10,000 Tibetan nuns.

You ask how my Buddhist practice resonates with my research—a question I hadn’t previously considered. While I deeply respect Buddhism, I can’t claim to be a serious practitioner. Perhaps my lack of immersion in Buddhist practice is precisely what led me to focus on the physical arrangements and sensory realities of this monastic community. Had I been a serious practitioner, I might have prioritized the extraordinary spirituality of the teachers, much like the other pilgrims at Yachen. Instead, my distance allowed me to remain grounded stubbornly in the material lives of the nuns within a supposedly hyper-spiritual environment. Of course, through years of close observation, I found myself pondering the fundamental nature of religious faith. After all, what drove the nuns to endure such harsh conditions was a genuine aspiration toward enlightenment. Ultimately, my prolonged ethnographic immersion ensured that while I stayed focused on the material, I never lost sight of the immaterial dimensions of their religiosity.

Isla: “The politics of tranquility” is your observation of Buddhist nuns in Yachen, including both Tibetans and Han people. It is an alternative or othering practice in everyday life, which is not fully assimilated into the state governance and the confrontational refusal. What is the moment you realized this key theoretical concept? How do you capture this lack of formality without imposing existing theoretical frameworks, such as anarchism?

Yasmin Cho: From a secular perspective, Yachen stood out as a thriving religious community established by an ethnic minority. More specifically, given the prolonged controls and restrictions by the Chinese state on Tibet since the 1950s, Yachen was a surprising political success, however temporarily, accomplished by Tibetans (more precisely, I argue, the Tibetan nuns). But I wanted to know: How did this occur? It seemed to me that the crucial difference in Yachen, which made it different from any previous attempts to create a viable religious community in Tibet, was the quiet and tenacious daily making-do of the Tibetan nuns. Young Tibetan women kept coming to Yachen, huts kept being built by them, and Yachen kept growing despite increasing restrictions from all sides. In Yachen, there were no loud or violent protests, no grand demands or visible forms of resistance; instead, there was ceaseless and quiet doing: building, repairing, decorating, traveling, and making by the nuns. While discourses regarding Yachen’s unusual success are often devoted to the roles of charismatic male teachers and wealthy Chinese disciples, the physical labor performed by the nuns has not been counted at all in what is viewed as glorious success. Despite the size of the population of nuns, their existence—let alone their contributions—remains largely invisible in these accounts. Understanding what the nuns were making, or the way they were producing Yachen itself, requires a different framework, since existing frameworks, such as everyday resistance, fail to account for these physical and mundane components. I use the politics of tranquility to capture what these women succeeded in achieving on a daily basis.

To state it more clearly, I define the politics of tranquility as an alternative form of political agency exercised by the nuns. This politics is quiet, material, and—crucially—indifferent to how the state tries to label it. It emerges when marginalized groups face power on an such overwhelming scale that this power tries to redefine who they are and who they cannot be. The politics of tranquility in this regard is the exercise of sovereignty over oneself, which is fundamentally different from resistance. Resistance usually implies a target; you are pushing back against an oppressor with the intention of overturning them. Someone who is practicing the politics of tranquility doesn’t react to repressive force but remains indifferent to it. Through the sheer tenacity of living, the nuns instead cultivate what I call minor forces—small, subtle shifts that can set the stage for macro-political change; this comes from a term I borrowed from Erin Manning’s (2016) idea of a “minor gesture.” By simply continuing to do and be without pausing—and by refusing to let external pressure determine their actions—they engage in forms of life that might look non-political to an outsider, but these very practices generate significant political outcomes.

Isla: “Padmasambhava’s sparkling golden body, erected on the high hill in Yachen, looks down into the valley with his wholesome compassion (figure 10). This giant statue gazes directly at Achuk lama’s bedroom and monks’ quarters. It is as if Padmasambhava has forgotten those who actually molded his body by laboriously carrying mortar and bricks to the hilltop for years, as if his blessings pour onto Yachen’s monks who are largely temporary residents but not onto the nuns who are Yachen’s permanent residents as well as its builders. The compassionate body of this ancient master on the hilltop, a sacred phallus soaring up to the heights, is unable to find his way back to the majority of his disciples living and building in the valley below who have yearned for his blessing for so long.” (Cho 2024, 61-62)

This is my favorite paragraph in the book, your poignant feminist critique of Tibetan Buddhism in a tranquil mood. I think your writing reflects the politics of tranquility. Could you share the story or thoughts that inspired you to write this?

Yasmin Cho: I appreciate that you sensed a politics of tranquility in my writing, an effect I hadn’t consciously intended. I first noticed the Padmasambhava statue on the hilltop in 2011, when only its base was taking shape. At the time, I didn’t understand the scope of the construction, but I found it unsettling that only the young nuns were tasked with hauling bricks and mud from the riverside to the summit. Where were the monks? Over subsequent annual visits to and a long-term stay in Yachen, the statue grew into a massive monument visible from miles away. Its completion transformed Yachen’s appearance, shifting it from a nomadic shanty settlement into something resembling a formal monastery. However, knowing the years of rotating labor the nuns endured, I was shocked by the statue’s orientation. From the nuns’ quarters, the figure is seen either from the side or from the back. The monument decrees, instantly and instinctively, who belongs at the center and who is relegated to the margins. The irony that the majority of Yachen’s residents—its actual builders—live outside that center is conveniently dismissed. Both figuratively and physically, the nuns remain behind once again. I was fortunate enough to observe the whole processes of the statue-building that involved years of labor by the nuns, their faith toward the statue, and the final product and its gaze. The story of the statue powerfully shows how Yachen was being built and how its actual builders were being dismissed at the same time. By documenting the statue’s construction, I wanted to redirect attention to these long-neglected builders. Ultimately, a story can often reveal these stakes far more powerfully than academic analysis can.

Isla: In Chapter 4 “New Gestures,” you carefully describe the gender structure in Yachen and highlight how their bodily presentations in annual exams and medical practice overturn the gender norm in Tibetan Buddhism. However, I deeply resonate with you that the gender norm in nuns’ mundane everyday life is more challenging to change, or for women. Do you notice any gestures in the daily lives of Tibetan nuns and their Buddhist practices? Do you have any advice on making gestures to shake the gender norm in mundane and material settings?

Yasmin Cho: Your question prompted me to rethink the nuns’ daily lives from a fresh perspective. In the chapter “New Gestures,” I focused primarily on how the nuns’ bodily presentations—typically viewed in conventional contexts—transform within specialized settings like medical training programs and annual exams. It is important to clarify that the presentations of medical nuns or exam takers are intrinsic to their daily lives and Buddhist practices. While these moments may seem sporadic—clinicians practicing for a few hours a day or exam takers performing on stage once a year—these scattered blocks of time are constitutive of who they are. They are periods when the nuns transcend their conventional selves. Beyond these formal settings, your question led me to consider new gestures within their spatial practices, such as building, repairing, and decorating. While erecting a small hut may seem like a mundane physical activity, it is far from purely functional. As I argue in chapter 3, the act of building and decorating is also the act of making a political claim to a space of their own—one in which they can be free from both state surveillance and monastic gender norms. Viewed this way, these spatial activities are undeniably new gestures within their daily lives.

As for your last question, if it refers to the nuns in Yachen, I am not in a position to offer advice on making gestures to shake the gender norms within the mundane and material settings of Yachen. However, in a general context, I would suggest that—just like the nuns—performing small actions repeatedly that facilitate moving one’s life forward, however insignificant or unsuccessful these actions might look at the beginning (again, “minor forces”). I would keep in mind here again a lesson from the Tibetan nuns from Yachen: that small daily actions for oneself, not reactions to the external situation, can nudge a situation toward a new possibility. The term gestures already carries a sense of subtlety and quietude; as I use it, it also requires bodily engagement. Repeated small and quiet physical actions in daily contexts have tremendous potential—they can even build a giant community, as the Tibetan nuns proved through Yachen.

Isla: Yachen underwent changes, demolition, and reduction after 2017. How do you view or carry your connection with this project? The preface is written in Okahandja, Namibia. What is your current project?

Yasmin Cho: Yachen’s dramatic changes were, in a sense, anticipated, by practitioners and visitors in Yachen, given the volatile political climate of the Tibetan plateau and the scrutiny faced by booming monastic communities. Larung Gar, another large encampment in Sichuan province, had been targeted by the government a year earlier; its size was halved, and thousands of monastics were forced to leave. Rumors had already begun to circulate that Yachen would be next. Despite the partial demolition of Yachen, I believe the politics of tranquility endured. The nuns I knew were likely to act and adapt to their immediate circumstances without overthrowing existing systems, without vocally criticizing mainstream discourse, and without agitating law enforcement. I was fortunate to experience Yachen at its peak and witness this politics of tranquility in its full expression. The demolition of Yachen—at once expected and sudden—served as a visceral, physical reminder of the Buddhist notion of impermanence. During my stay, I built a tiny hut in the heart of the nuns’ quarters where I slept, ate, and wrote my field notes. That structure vanished in a single day along with those of my neighbor—as well as my neighbors themselves (they were forced to leave). Perhaps the sense of security and stability is indeed an illusion—an attachment of the mind, as Buddhism teaches. In this light, Yachen’s presence and its subsequent absence are, themselves, embodiments of living Buddhist knowledge, which I experienced firsthand.

Politics of Tranquility engages deeply with the field of material religion, emphasizing mundane, bodily, and sensorial practices. I am now applying this same focus on mundane, bodily, and sensorial practices to the question of whether—and how—Buddhism functions as infrastructure in the context of Chinese Buddhism’s global transmission in China’s increasing presence in the Global South. I encountered an NGO that originated in Taiwan and had connections to Sinophone regions across Asia. It was spearheading development and charity initiatives in several sub-Saharan African nations. My fieldwork took place on their school campuses (Namibia and Madagascar), where they have established boarding schools for vulnerable African youth. My interest in the material and everyday aspects of life continues to drive this project, particularly as it intersects with the discourse on Global China. There is also a fascinating recursive element: The project circles back to Tibetan Buddhism, because the NGO invites many Tibetan monastics to participate. There is still much to explore, but for now, I am looking at the exciting interplay between the global transmission of Buddhism, cross-strait geopolitics, and the relationship between faith and doing good.