Interview by Georgia Ennis

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo28179073.html

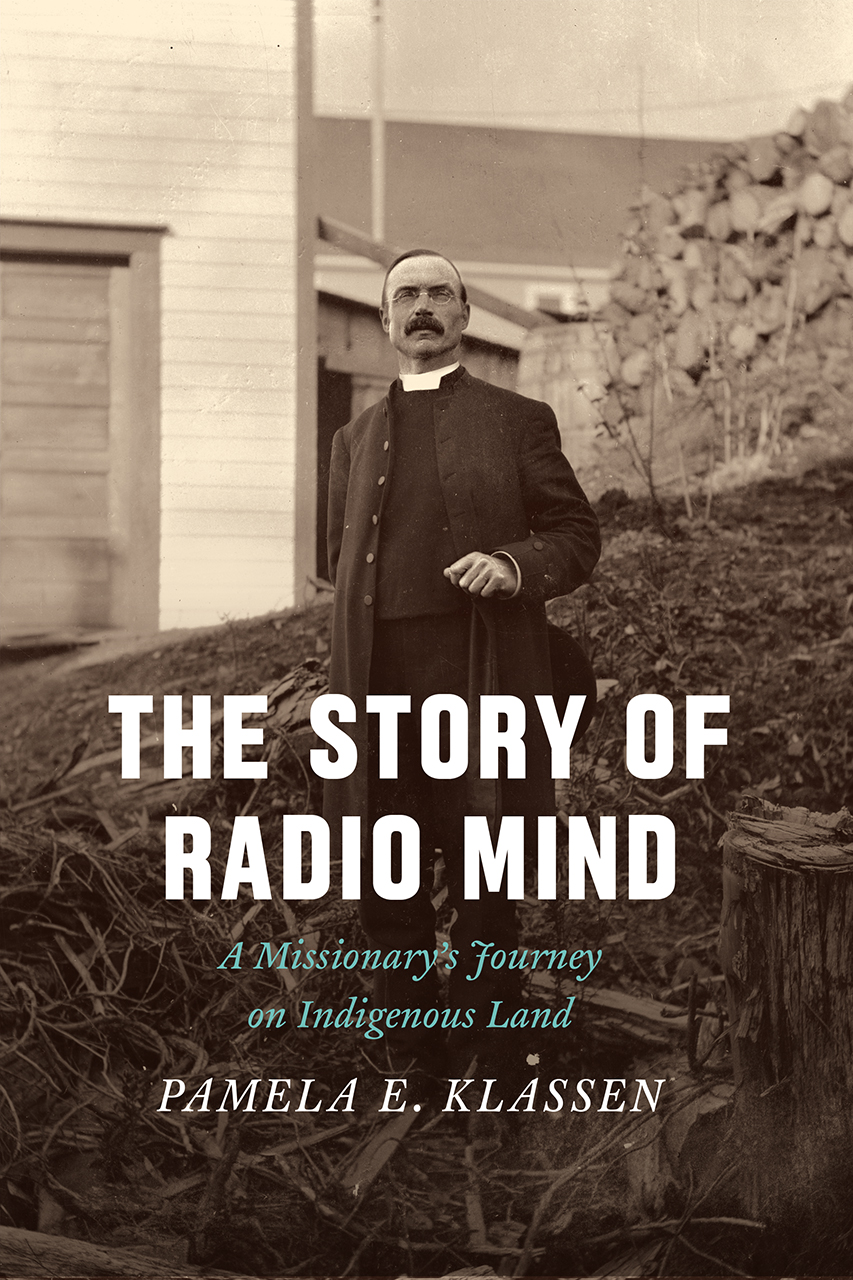

Georgia Ennis: At the center of your account are the travels and work of missionary Frederick Du Vernet, with whom you speak across time in numerous ways. How and why did Du Vernet come to be the central personage of this story of settler colonial expansion? You describe your first ‘encounter’ with Du Vernet in the text, but can you tell us more about how you came to travel with him and his many contradictions across what is today known as Canada?

Pamela Klassen: I first encountered him through reading newspaper, church newspaper articles for another book I was writing on Christianity and medicine and healing in the 20th century. And they were very unusual articles that were uncommon for an Anglican newspaper in the 1920s, in which he was basically propounding his theory of telepathic thought transference. He also had a kind of theory of media he was writing about, like the new effects of the cinema, and what this would do to young hearts and minds. By the mid-1920s, he was writing about his new theory of spiritual radio or radio mind — basically the idea that human beings can transfer their thoughts across this energy field, radio waves that God has provided for us as a means of communication. He’s coming up with this theory at a time when a few people have radios. He is doing what is a very common approach by taking a new technology and spiritualizing it. This happened with the telegraph and the telephone, with all these kinds of means of communication.

I went to the national church archive in Toronto to see if I could find out more about him. And the archivist, very kindly pointed me to a diary that he had written in 1898 when he was a missionary journalist who was travelling across Canada and visiting different missionaries and missions along the way. This diary records 11 days of his visit to the Rainy River, which was an area fairly newly settled by white settlers. It was on an Anishinaabe territory or Ojibwe territory.

It was a remarkable diary because the way he writes it, he writes often in the voice of Anishinaabe women and men he encounters. Often older women and men who were quite resistant to his presence, even their words are his perspective. It struck me as a really powerful record of Anishinaabe resistance to Canadian and Christian presence on their land. I put thae diary aside, finished the other book, and then the diary was really haunting me. Eventually I said, “You know, I wonder, maybe I should actually figure out if I can go up there and bring the diary back to where it was written.” When I did, I met with some very kind members of Rainy River First Nations, especially Art Hunter and his brother Al Hunter, and since then, I’ve been going up regularly. We now have a website where I talk about the diary. That’s been one life of my encounter with Du Vernet.

I guess one thing I would say is, it’s rightfully very challenging for a white woman to write about indigenous missionary encounters and, and indigenous sort of state relations in the Canadian context, but I also felt it was my responsibility to write about the Canadian side of that history. He was allowing me to also challenge my field of the study of religion that often looks especially at North American religion, that will often look at a man like him as someone participating in a new religious movement. But he wasn’t. He was an Anglican through and through, he was an Archbishop. He was a mainstream Christian man, but also the ideas that he came to emerged from his relationships with indigenous people across Turtle Island, across Anishinaabe and other nations. And focusing on him allowed me, as a white woman, to tell a story of white people’s responsibility for the world that we live in today.

Georgia Ennis: Themes of testimony, confession, and reconciliation, as well as the ways these genres have been understood within different linguistic and cultural traditions, are central to the book. What kind of testimony do you envision The Story of Radio Mind providing, and what is its relationship to ongoing processes of reconciliation within Canada and other settler colonial states?

Pamela Klassen: A great question, thank you. I began writing the book before the Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation commissions’ final report came out in 2015, which was a Truth and Reconciliation Commission focused on the church-state nexus of residential schools, schools that indigenous children were often forcibly taken to, often by the police, the RCMP. They were largely paid for by the Canadian government, but run by different churches. So, you would have an Anglican or a Methodist or a Catholic school. So, the discourse of reconciliation is very much of the moment in which I wrote the book, and still present was when it came out in 2018. Now we are in 2020. And the discourse of reconciliation is clearly not sufficient. At this moment, June 2020, we’re addressing questions of the ongoing, not just legacies, but reality of colonialism and in Canada and the US and how that connects to anti-black racism and anti-indigenous racism and police brutality. Its important for scholars to have a kind of awareness of the moment in which they’re writing but also a kind of humility knowing that the things they write two years ago will have a different resonance and you can’t know what that’s going to be.

Questions of testimony and confession were really alive in the cultural moment in which I was writing, because a Truth and Reconciliation Commission is profoundly a moment of testimony. There really was not a lot of confession going on, because it was mostly indigenous survivors, telling their stories and giving their testimonies. Still, the very notion of reconciliation, which I discussed a little bit in the book, is from one kind of understanding, a profoundly Christian concept and it’s still a Christian ritual – about forgiveness and becoming, restoring your relationship with God. The fact that a state-based ritual of Reconciliation has these Christian roots I think is worth pondering.

I also like to think about what can become appropriate anthropological stories about these places, and how anthropologists were similar to missionaries in that both anthropologists and missionaries sought stories out of the indigenous people that they encountered. The anthropologist turned them into ethnography, the missionaries turned them into stories that they could package in church newspapers and missionary newspapers so that they could get more funding for their missions. The anthropologists also wanted funding from the Smithsonian, or other sources. So the whole question of “stories for cash” was something I wanted to think about. And which, of course, I’m implicated in as well.

Georgia Ennis: You close the book by reflecting on another kind of medium, the body. Yet, you consider throughout ways in which various media technologies interact with, shape, and otherwise mediate bodies or embodied relationships, from photographs and accounts that “firsted” and “lasted” Indigenous peoples out of existence, to spiritual frequencies said to have connected minds across great distances. How do you envision the interrelationship among the various forms of mediation you examine—embodied, spiritual, and technological? What effects do they have on each other? And, relatedly, do you have any thoughts on the role of digital or supposedly “new” forms of mediation, and the future of the stories you examine here?

Pamela Klassen: Sure. Yeah. I mean, I should say, I guess, that I think about – since we started our informal part of the conversation talking about midwifery, my earlier work was on midwifery and women’s experiences of childbirth, and how, in the North American context, a lot of women turn to midwifery for very different reasons. Sometimes they do it through legal means, illegal means, grey area, law, that kind of thing. And so, when I worked on that project, it was the 1990s. So, it’s a different sort of midwifery landscape than there is now. But I always really thought of myself as someone who thinks a lot about the body, gender, racialization, and these kinds of things. And then I found myself writing a book that was all kind of channeled through the body of this man who was a white Christian missionary, and sometimes I worried that I wasn’t paying enough attention to the body. Yet one of the things that I really want to want people to take away from the book is realizing that whiteness was a very active category at this time and it was a lived reality. So, when Du Vernet gets to Northern British Columbia in 1904, he was doing what the missionaries call Indian work. He was working with indigenous people who are there. But he arrives there at the same time that the railway is getting going, because they want to build a railway for all kinds of complex reasons, to this point, in Prince Rupert, because it’s got a very deep harbor and they see Prince Rupert as being the gateway to Asia, also the gateway to the north, and also a competitor to Vancouver and Victorian San Francisco. It’s the crawl of the railway, the spinal cord of colonialism. By the time he’s at the end of his life, he is doing what everybody calls “white work”, which is working with the settlers. He is aware, he talks a lot about the differences, the challenges of doing both Indian work and White work. Whiteness is a very active animating category for settler colonialism. I think people often don’t realize how freely people spoke with these racialized terms across North America in different ways, and with different differences.

One of the things I also wanted to point out is that all of these communication tools depend on matters that is drawn from the earth, the minerals in our cellphones, in our computers, stuff that makes our cellphones, and our computers. The cloud is not a cloud, its actually made out of servers that require cooling and heating, demanding vast resources to actually keep our communication systems alive. I wanted to frame and draw attention to the fact that all forms of mediation and communication have consequences for the earth and for the world, and therefore for us, and all the creatures on the earth.

Then, just to end briefly with a website I would love for people to go and look at: https://storynations.utoronto.ca/. On this site, we take the diary that I was talking about earlier, and we annotate it. We try to put it in the larger historical context of Treaty 3, in relationship between missionaries and Ojibwe in that context. We visit the community quite often to talk to them about ideas and about where to go next. So soon we’ll be trying to build curriculum resources, so people can use it on their online teaching that they have to do in the near future, both in high schools and in universities. We are doing a pilot study with indigenous youth students to get feedback from them about how this website tells the story of colonialism of indigenous presence and continuity on the land and what we learn from it. We welcome anybody to visit and learn from the website. And it was actually very interesting to write about this story in two different forms — in the book and the website. The book is done, not clear if the website will ever be done.