No matter the size of shows, and the actual count of the public, the Indian circus works hard to appear larger-than-life. The image of the circus, in other words, is in many ways larger than the show itself, the publicity that fuels it traveling ahead and enticing expectant crowds before a company’s arrival. The circus and its image bleed into each other, they exist symbiotically; when one is attacked, the other suffers with it.

In my dissertation, I track the ongoing disappearance of the circus in India as performances get associated with accusations that prove increasingly difficult to shrug off, including charges of animal mistreatment.

On P. 99, I locate one such shift in the public’s perception of the circus to a period from 1988 to 1998. Drawing from reports and opinion pieces appearing mainly in the Times of India, I track animal rights NGOs’ strategies as they shifted from earlier suits against individual street performers and animal tamers to large-scale reports and rescue operations targeting itinerant circus companies. Because the public did not tend to differentiate between one company and another, these strategies ultimately led to the entire profession being seen as complicit, at all levels, in the mistreatment of animals.

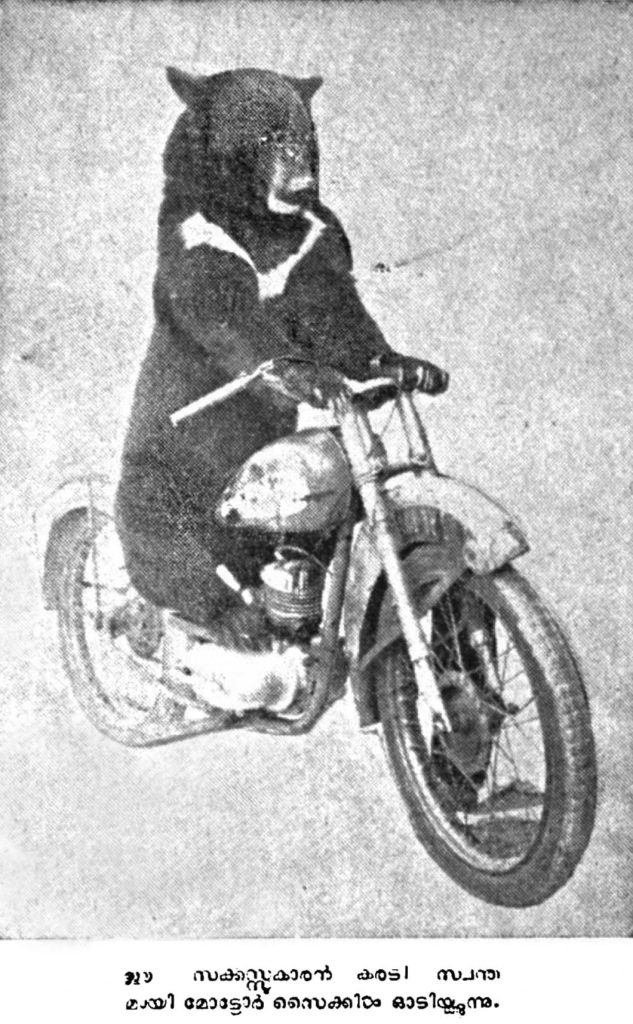

Caption (translated from Malayalam): This circus bear rides a motorcycle by himself

Source: Mathrubhumi weekly, January 1955.

P. 99 also notes the class disparities that mark the stark divide between the ideals of interspecies ethics that exist among circus practitioners and the more abstract notions of humane treatment and harm stipulated by members of animal rights organizations removed from the material conditions of work with animals.

Interestingly, both sides play upon the image of animals and humans working side by side in the circus foregrounded by circus publicity: one in the name of sociality, the other in the name of exploitation. Both also invoke the motif of the circus’s disappearance to their own end—one to harken back to the circus’s former glory and bestow upon it the mantle of an expiring art form, the other to look forward to a future in which its practices have been definitively relegated to the past.

Ironically, I claim, both sides, in insisting on the circus’s disappearance, have contributed in their way to sustain the ongoing presence of this performance, whose survival now seems predicated precisely on its being an object of dispute, always disappearing, yet never out of view.

Eléonore Rimbault. 2022. Disappearance in the Ring: The Perpetual Unmaking of India’s Big Top Circus. University of Chicago Phd.