by Kristiana Willsey

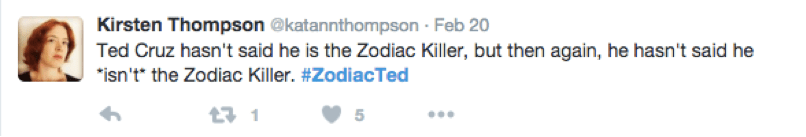

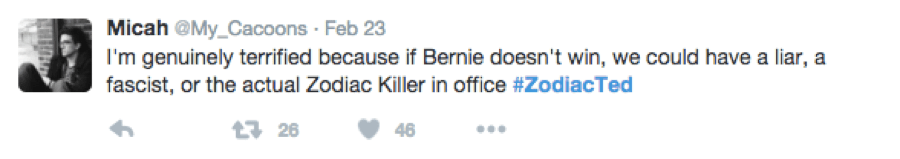

There’s a story circulating online that Ted Cruz is the Zodiac Killer. More accurately, there’s a story that there’s a story Ted Cruz is the Zodiac Killer—the twitter-originated conspiracy theory isn’t attached to a clear canonical narrative, and like many viral sensations, it’s impossible to separate the appeal of the joke itself from the buzz surrounding it. In other words, everyone is talking about how everyone is talking about it. Type the words “Is Ted Cruz” into Google, and the traffic-driven algorithm helpfully supplies “the Zodiac Killer.”

Undeterred by evidence that Ted Cruz was a four-year old child living in Canada at the time of the last confirmed activity of the Zodiac Killer, the story has been picking up steam for the past few months, spurred by the blithe, ironic conviction of twitter comedians.

It received a bump at the end of February, when activist Tim Faust began selling T-Shirts and donating the proceeds to West Fund, a non-profit that helps fund affordable abortions in El Paso, Texas.

It received a bump at the end of February, when activist Tim Faust began selling T-Shirts and donating the proceeds to West Fund, a non-profit that helps fund affordable abortions in El Paso, Texas.

In an interview with Broadly, (the female-focused branch of Vice), Faust explains, “Folks have been making “[unlikely person] is the Zodiac” jokes for a long time. (I know Letterman made one in 2002 and surely there have been more before that.) But some folks I follow on Twitter had been joking about Ted Cruz being the Zodiac Killer off and on for a few weeks, and I thought it was both interesting and plausible.”

Faust is doing what folk artists have always done: identifying a recognizable genre of expressive culture and reinventing it, investing his new iteration with contemporary relevance and political bite. Faust contends that the virality of the story rests, not on the incongruity of its claims, but on its sneaky “plausibility.” It’s funny because it’s “unlikely,” but it’s traveling via a perceived semantic overlap of the 1960s serial killer and the affectless Republican presidential candidate. “Realistically,” Faust says, “the Ted Cruz indirect body count (by rejecting Affordable Care Act expansion, anti-choice ideology, etc) is way higher than anything the Zodiac could have dreamed.”

Cynics might be quick to dismiss #ZodiacTed on the grounds that no one really believes it. But it isn’t belief that’s the litmus test for legend, it’s believability—a degree of ambiguity is what gives a good story legs. Rumors are circulated most aggressively not by the true believers, but by the incredulous, who spread the story as they seek to verify that it isn’t true (Dégh and Vázsonyi 1973). No story could offer better proof of Linda Dégh’s statement that “it does not necessarily change the quality of the narrative if the narrator is a nonbeliever or a defeatist who produces an anti-legend to kill the story” (Degh 2001: 311).

Far from killing the story the legend has, characteristically, thrived on uncertainty and even irony. According to a poll conducted by Public Policy Polling (also recently in the news for their poll finding that 41% of Trump voters support bombing the fictional Disney city of Agrabah), 28% of Florida voters are “not sure” whether Ted Cruz is the Zodiac killer, while another 10% are certain that he is. Obviously there’s no way of knowing who answers a survey honestly, but sincerely or ironically, the bulk of people circulating the story are trading on its “plausibility”—it isn’t true, but it feels true. In a word Stephen Colbert coined for situations exactly like this, it’s “truthy.”

At first glance, the meme seems a bit too skimpy, too lacking in formal narrative qualities to even qualify as a contemporary legend. We might call it rumor, which is “usually brief and does not necessarily have a narrative element […] A legend may be regarded as a solidified rumor” (Allport and Postman, in Mullen 96). But as Patrick Mullen points out, “It would be a mistake to distinguish severely between rumor and legend […] some legends become rumors and some rumors become legends,” depending on the length and detail of the performances (Mullen 96, 98).

Instead, the joke is a one-size-fits-all narrative abstract, which individual tellers can use as a springboard or conversation starter. Contemporary legends are best understood as process rather than product, a “body to be ‘clothed’ in performance … in order to provide a vehicle for the discussion of relevant contemporary issues” (Paul Smith in Brunvand 2012). The efficiency of the six-word joke is part of what makes it so shareable, but it’s spawning ever more elaborate narrative explanations, from the simple (an image of Ted Cruz alongside Munsters actor Al Lewis, “proving” Cruz is an ageless vampire)—to the complex (a 28 page-long e-book the author describes as “terrifyingly erotic”).

Snapshots of online conversations underscore the point that, whether the narration is virtual or embodied, legends are collaborative performances. The story attached to ZodiacTed isn’t a singular, static work of art, but a spontaneous, emergent dialog: “the legend is more controversial than other genres, and a true legend-telling event is not therefore the solo performance […] It is a dispute, a dialectic duel of ideas, principles, beliefs, and passions” (Degh and Vazsonyi 1978:253, also Shibutani 1966, Ellis 2001). Since belief is a continuum, we can’t discount debates about whether Ted Cruz is a time-traveling baby, the serial killer reincarnated, lizard people, or some combination of all three.

Part of the story’s appeal is the impossibly fine line between ignorance and irony, a “fight fire with fire” foil to the emotionally charged, dubiously factual political rhetoric of other candidates. A recent article for the Washington Post discusses Trump’s “campaign of conspiracy theories”—birtherism, the vaccines-to-autism connection, claims of cheering crowds of Muslim Americans after 9/11—pointing out that Trump’s sincere belief in these snowballing stories is less relevant than how successfully he is using them to mobilize the anger and confusion of his fan base.

In a world where Donald Trump’s candidacy has been called a publicity stunt, a hoax, or performance art, anything goes—if that joke came true, why shouldn’t this one? Those feeding the rumor cherish hopes of Cruz being forced to address it publically, puncturing the play frame and elevating the joke from absurdist throwaway to genuine controversy.

In a world where Donald Trump’s candidacy has been called a publicity stunt, a hoax, or performance art, anything goes—if that joke came true, why shouldn’t this one? Those feeding the rumor cherish hopes of Cruz being forced to address it publically, puncturing the play frame and elevating the joke from absurdist throwaway to genuine controversy.

Like Dan Savage’s successful campaign to take gay marriage-opposing senator Rick Santorum’s last name and turn it into one of the more visceral entries in urban dictionary, ZodiacTed’s success rests on a savvy manipulation of the ever-narrowing space between the real world and its digital record.

Like Dan Savage’s successful campaign to take gay marriage-opposing senator Rick Santorum’s last name and turn it into one of the more visceral entries in urban dictionary, ZodiacTed’s success rests on a savvy manipulation of the ever-narrowing space between the real world and its digital record.

In the inevitable muddle of digital orality, some websites have already historicized parts of the legend. Fan site The Mary Sue reported, with seeming earnestness, that the hoax originated from Cruz’ inexplicable decision to title a 2013 CPAC speech, “This is the Zodiac Speaking,” which would certainly be suspect, if it were true. The commentariat was quick to jump in with corrections: the title of the speech is a now years-old twitter joke by Red Pill America, credited with starting the rumor to begin with.

In the inevitable muddle of digital orality, some websites have already historicized parts of the legend. Fan site The Mary Sue reported, with seeming earnestness, that the hoax originated from Cruz’ inexplicable decision to title a 2013 CPAC speech, “This is the Zodiac Speaking,” which would certainly be suspect, if it were true. The commentariat was quick to jump in with corrections: the title of the speech is a now years-old twitter joke by Red Pill America, credited with starting the rumor to begin with.

As digital worlds become increasingly interwoven with our everyday lives, enterprising app designers offer creative fixes for re-writing your life: replace the babies in your Facebook feed with cats! Use this Chrome extension to swap the word “millenials” with “snake people!” Now, you can combat the powerful, persuasive connotations of “Trump” by changing all web-based instances of his name to “Drumpf.” Go edit IMDb and Wikipedia to reflect your new reality.

As digital worlds become increasingly interwoven with our everyday lives, enterprising app designers offer creative fixes for re-writing your life: replace the babies in your Facebook feed with cats! Use this Chrome extension to swap the word “millenials” with “snake people!” Now, you can combat the powerful, persuasive connotations of “Trump” by changing all web-based instances of his name to “Drumpf.” Go edit IMDb and Wikipedia to reflect your new reality.

If what you see (retweeted, remediated, always already narrativized) is what you get, you may as well do what you can to make your personal virtual world a little more surreal.

Kristiana Willsey has a PhD in Folklore from Indiana University, and teaches at UCLA and Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles.

References

Allport, Gordon W. and Leo Postman. 1965. The Psychology of Rumor. New York: Russell & Russell.

Brunvand, Jan. 2012. Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, 2nd Ed. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Dégh, Linda. 2001. Legend and Belief: Dialectics of a Folklore Genre. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Dégh, Linda and Andrew Vázsonyi. 1978. “The Crack on the Red Goblet or Truth and Modern Legend.” Folklore in the Modern World, ed. Richard Dorson. The Hague: Mouton.

_______________________________________. 1973. The Dialectics of the Legend. Bloomington: Folklore Preprints Series, no. 1.6.

Ellis, Bill. 2001. Aliens, Ghosts, and Cults: Legends We Live. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

Mullen, Patrick B. 1972. “Modern Legend and Rumor Theory.” Journal of the Folklore Institute 9 (2/3): 95-109.

Shibutani, Tomatsu. 1966. Improvised News: A Sociological Study of Rumor. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.