by Erika Alpert

Krakoan national co-founder Magneto explains to diplomats at the new Krakoan Embassy in Jerusalem why mutants have decided to create their own language, from House of X #1 (Hickman et al. 2019a, 32).

In 2025, wars are raging in Ukraine and Israel and too many other places, but they all come down to which peoples and lands are “real countries,” and which are merely conquered or conquerable populations and territories to be managed. As I try to make sense of it all, a person whose Slavic and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestors came together in early 20th century Detroit because they all really hated the Russian empire, I can’t stop thinking about the X-Me

Stay with me.

Since folklorist Johann Herder’s work in the 18th century, language is widely understood to be a fundamental part of what makes nations distinct political and cultural entities. Language is why France is France, Spain is Spain, and Portugal is Portugal. Except, as linguists know, this isn’t how language works. Europe, like much of the world, is covered in dialect continua with neighbors in nearby towns and villages speaking recognizable varieties that form points along a gradient rather than distinct languages with clear boundaries. Provençal, Catalán, Gallego, and other local Romance varieties form exactly such a continuum from Iberia to Belgium (Chambers and Trudgill 1998, 5).

But we believe this to be true: a nation is an expression of the political will of a people with a shared culture, shared lands, and shared language, together with its repertoire of shared stories and songs, customs, habits, and all the things that set one ethnic group apart from another. Not only do we insist on these differences—we plan them and we create them and we police the boundaries between languages as a semiotic means for remaking territorial borders on a different scale (Irvine and Gal 2000).

The European examples are what I give students in introductory linguistics classes, but my own practical experiences with language planning and policy are mainly post-Soviet, from the years I spent working at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan. The USSR fell apart when I was ten. One thing I remember from the 1990s is endless jokes about confusing new maps containing a gajillion new countries that no one had ever heard of before—which they hadn’t, and for good reason. Many former Soviet republics were carved out of contiguous territories occupied by related peoples, and didn’t exist as separate countries before the USSR. But for assorted governance reasons, Soviet ethnographers and linguists took Russian imperial lands and drew new boundary lines around peoples, languages, and territories, producing “Kazakh” (or “Qazaq,” as many Qazaqs prefer), “Kyrgyz,” “Uzbek,” and “Turkmen” out of the different Turkic varieties spoken across Central Asia. The goal was to give each language and ethnicity its own mini-nation within the federal framework of the USSR. (Waite 2020 has a good overview of this process).

Kazakhstan, just south of Siberia, has the dubious distinction of being the most ethnically diverse post-Soviet state, because it’s where all the “undesirables” were deported (Lillis 2017). And despite all that linguistic and ethnographic labor, the Soviet government changed its mind about the value of promoting national languages and cultures within its territories, and Russification proceeded apace after the 1930s. In the post-Soviet era, these nations have to contend with this legacy of Russification. At the same time, they also have to elevate and promote their national languages in order to justify their continued existence as separate nations. Far from being abstract or theoretical, Russian premier Vladimir Putin has used the argument that Ukrainians are basically Russians, and the Ukrainian language is also basically Russian, as an argument for invading Ukraine. Demonstrating the linguistic distinctiveness of Ukrainian language and culture is literally a question of life and death (Carter 2022).

I moved to Kazakhstan in August 2014, some months after Putin’s forces first annexed Crimea. “Oh shit, we’re next” was a pretty common sentiment in Kazakhstan at the time, with its Russified north, high percentage of ethnic Russians (around 20% of the population), and lengthy border with Russia. It is unofficially but widely acknowledged that the capital was moved from Almaty, far in the south, to Astana, smack dab in the middle of the country, in order to encourage ethnic Qazaqs to migrate north. Russian is the first language of many Kazakhstanis, regardless of ethnicity, and is an auxiliary official language.

Like Ukraine, the Kazakhstani government has an existential interest in promoting Qazaq language and culture. It helps that Qazaq is Turkic, not Slavic, and therefore considerably more linguistically distinct from Russian. But given its very diverse population (ethnic Qazaqs are now just over 71%), the government also has to disentagle Qazaq language from Qazaq ethnicity and link it instead to Kazakhstani citizenship. This is one of the reasons that Nazarbayev University exists. A certain level of Qazaq language proficiency is a requirement for all graduates, regardless of ethnicity, and the Qazaq language department is busy and large.

So why can’t I stop thinking about the X-Men? Because the X-Men live in an improbable fictional world, populated by people with extraordinary abilities, they get to do weird things like exemplify moral and cultural ideals about what nation-building and language planning could or even should look like in a more fantastic world. As with much speculative fiction, the story of the founding of Krakoa illuminates what real nations do, why they do it, and where we think we fall short in our real-world attempts to convince others that we deserve sovereignty, security, and political recognition. The X-Men get to do what independent post-Soviet republics want to do—what any aspiring ethnic state wants to do—and they get to do it better, faster, and frictionlessly. As Karlander (2025, 85) asserts, “the creation of a micronation implies an intensified commitment to statehood and the semiotics of statism, not least in their manifold nationalist guises. The micronational mimesis of state power thus enacts a specific critical stance, that is: critique without critical distance.” Micronations, real and fictional, engage in language planning, and sometimes language creation, precisely because a new nation is still a nation, and therefore needs all of the trappings of one, even if ad-hoc, satirically, or fictionally.

I’m going to assume that you know who the X-Men are if you’ve had any contact with English-language pop culture in the last 30 years. But unless you’re a really big fan, you probably don’t know about Doug Ramsey, aka Cypher. Doug’s mutant power is basically speed linguistics. He’s not well known or beloved, although the guy at my local comics shop did inform me that he’s going to be at the center of 2025’s big X-men crossover event. (Thanks, writer Jed McKay, I owe you one.) Doug’s a cute blond boy who looks like a normal human, and can’t do anything flashy or combat-oriented. His powers mostly camouflage themselves as seeming really smart. Doug’s mutation doesn’t help him learn languages instantaneously or psychically get past language barriers to communicate. He can just analyze language very quickly compared to real field linguistics. This is made most clear when Professor X, circa 2019, assigns Doug to make friends with a sentient island and learn his language, to see if the living land will itself consent to be transformed into a paradisiacal mutant island nation.

Professor Charles Xavier, telepathic mutant leader, introduces Doug Ramsey to Krakoa, the living island, in Powers of X #4 (Hickman et al. 2019c, 16).

Why might mutants want their own nation? The basic premise of X-Men is that the higher radiation levels of the atomic era created more people with inborn super-powered mutations, as opposed to acquiring superhuman abilities later in life after transformative encounters with cosmic rays, radioactive spiders, or toxic chemical sludge. As the comic develops its premise from the 1960s into the 1980s, these mutations are pinned by writers not just on ambient “radiation” writ broadly but on a specific “X-gene” that gives every mutant a shared genetic heritage.

Superheroes like the Fantastic Four are small teams held together by ties of kinship, friendship, and shared traumatic cosmic ray experiences. However, the hereditary quality of mutant powers and physiology makes mutants a large cohesive group, like an ethnic minority. Politically and biologically speaking, they are seen as born this way. This makes them uniquely appealing targets for eugenic discrimination and exploitation, depending on whether the people around them think mutations are good or bad, and whether they envy mutants or want to eradicate them. Pop-culture commentator, writer, and activist Jay Edidin (along with podcast partner Miles Stokes) has specifically called this “the mutant metaphor,” enabling mutants to stand in for whichever marginalized group an author might want to tell a story about: ethnic minorities, gender and sexual minorities, people living with disabilities (Ackerman 2018). Because of mutants’ textual and allegorical properties as a cohesive group who face unique discrimination, they tend to stick together.

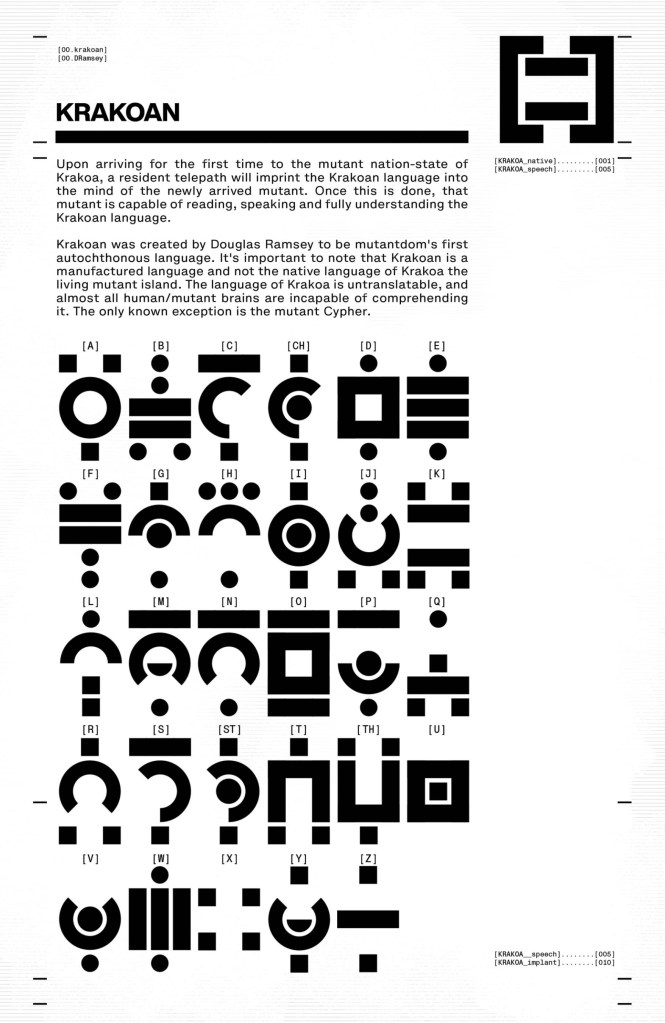

Much like real marginalized populations, some mutants espouse the virtues of nationalism or separatism, which produces enclaves like villain Magneto’s mutant supremacist Acolytes, or microstates like Genosha in the 1990s or Utopia in the 2010s. Doug Ramsey’s assignment to make friends with the island of Krakoa is actually mutankind’s third attempt at nation-building. Krakoa is different in large part because it’s planned. Genosha and Utopia were created opportunistically and haphazardly, governed by authoritarians with minimal political structure. By contrast, Krakoa has a government, and not just a self-appointed leader. It has laws. It has a security apparatus (and the comic dedicated to it is one of the most horrifying things I’ve ever read). But perhaps most importantly, it has a language. The language is not the island’s own native tongue, which Doug does learn. In fact, no one else can speak to Krakoa directly, which gives Doug a special position in the government as the voice of the land itself. But the mutant national language, Krakoan, is Doug’s creation, and it’s psychically taught to every mutant who passes through the living gates that teleport them to and from and around the island.

Information page explaining Doug’s linguistic accomplishments and showing the Krakoan alphabet, from House of X #3 (Hickman et al. 2019b, 30).

A world with language superpowers and instantaneous, telepathic language learning means that mutants don’t need Krakoan to communicate with each other. The X-Men has featured many US American characters, but it also has Latin American, Québécois, Russian, Kenyan, Indigenous American and Australian, Japanese, and Afghani characters—lots of mutants whose first or preferred language might not be English. But mutant telepaths can and do teach everyone else any language they might need. Before Krakoa, being a mutant means being cosmopolitan polyglot. But, as we see so often in antisemitic rhetoric, being a cosmopolitan polyglot is the opposite of being a citizen of a shared nation with a shared cultural heritage (Barenblat 2018). Jews are never really citizens of the countries where they live—and neither, it seems, are mutants.

If mutants want to be taken seriously as a people, with the right to determine their own political destiny, then they need all the recognizable trappings of peoplehood. Magneto’s statement that mutants need a shared language to build a shared culture in order to eventually be a real nation is not true, as a matter of linguistic or anthropological fact, but it’s also an understandable impulse that reflects how nations legitimate themselves in real life.

It’s not an accident that Magneto, long-time mutant defender and separatist, shows up in Jerusalem to formally announce Krakoa’s founding to the diplomats of the world. He is famously a German Jew and Holocaust survivor. Israel is the place where he originally met his best frenemy and ex-boyfriend, Professor Charles Xavier, leader of the X-Men. The X-Men’s politics, and Magneto’s in particular, have often reflected internal Israeli and diaspora Jewish politics (Elbein 2024). It’s not an accident that part of the Zionist project to create Israel involved reviving Hebrew as an everyday language while actively rejecting the hybrid languages that Jews developed in diaspora: Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic (Schweid 1984). Likewise, I’m sure it’s not an accident that, in building Krakoa, mutants too reject multilingual, diasporic language practices. And it’s probably not an accident that Krakoa is a nation that can be built without a Nakba, founded on consenting, sentient land that offers itself up as a home for mutants (Goldsmith 2020). Krakoa is nation-building done right, or at least, an attempt at it.

Marvel Comics are not JRR Tolkein, nor HBO, nor Star Trek, and they did not hire anyone to come up with an actual Krakoan language. In the comics, it’s represented with an alternate alphabet that only loosely diverges from English Latin in its character inventory. But although it’s just a cipher, it clearly stands in for an actual different language in the comics, unintelligible to others, as when mutant characters speak in Krakoan to each other to communicate when being surveilled or in hostile circumstances.

Mutant gladiator Shatterstar says “hi” to mutant detective Polaris in Krakoan. X-Factor #3 (Williams et al. 2020).

Language is not mutants’ only cultural endeavor. On Krakoa, mutants work to cultivate mutant fashion, literature, and perhaps most notably, mutant religion. They work towards mutant-specific visions of justice and peace, of accountability, of sexual ethics and relationships. But by their own account, it is a shared mutant language that makes this possible, that makes mutants a people, a nation, and not just a motley collection of freaks. The vision of Krakoa requires a linguist to negotiate with the island, to speak for the island, and finally to design their utopian language and fashion a script for it, not unlike the literary standards and scripts created for the newly distinguished Turkic languages of the USSR. It requires a rejection of the cosmopolitan and embrace of the monolingual, the pastoral, the folkloric, as mutants elaborate their own national mythology, and comics writers deepen the lore, writing and rewriting our own modern myths. Magneto, the villain of X-Men #1, is now one of Krakoa’s greatest heroes.

With all of this said, large comics franchises never really end, and no matter how much their characters go through, they are only gently, ever so slowly, allowed to age and learn and grow. At the same time, what drives stories is conflict, which means that a tropical island paradise that all mutants can safely call home cannot be allowed to last. Internal discord and external attacks destroy the nation. The First Krakoan Age is over. But it seems like memories of Krakoa will live on. Most mutants still know Krakoan, and as they scatter into diaspora once more, I can’t help wondering whether the language will still be allegorically and narratively useful for bringing mutants together. Now we get to find out what comes after nationalism.

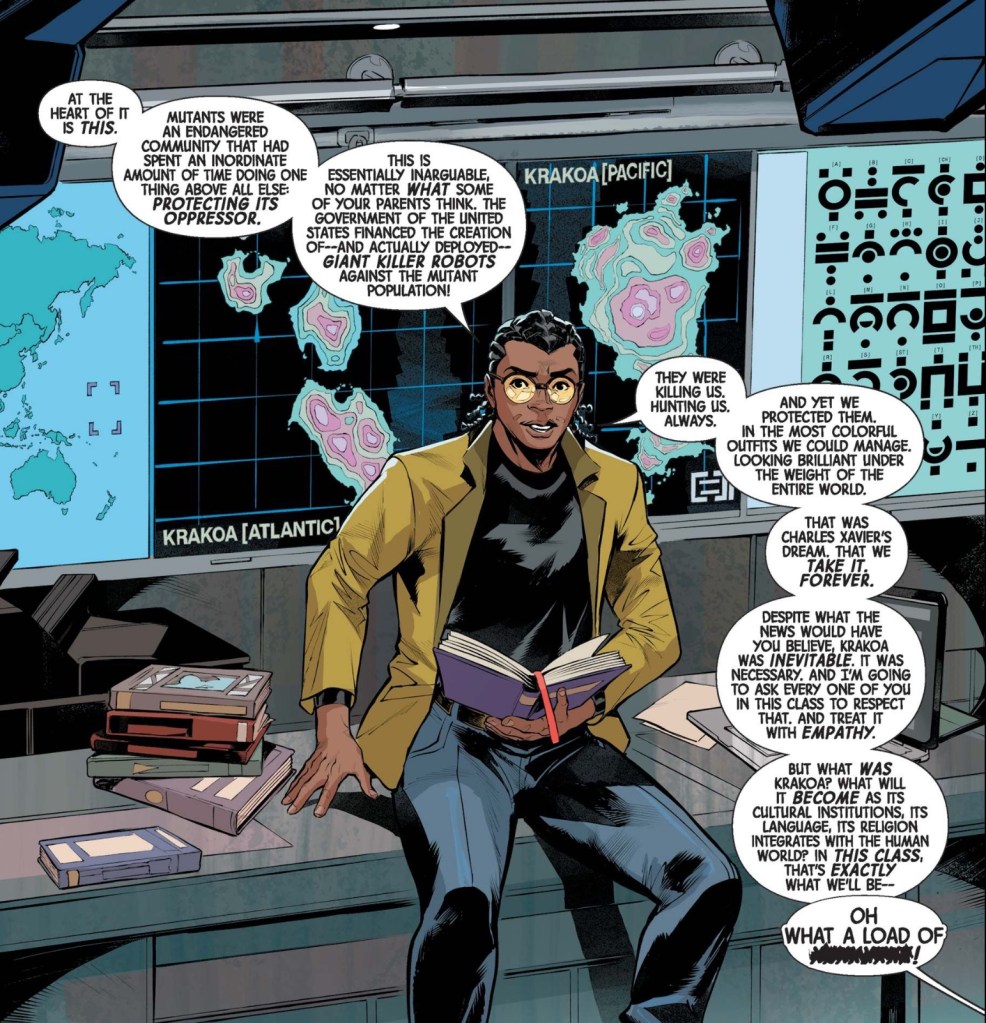

Mutant scholar David Alleyne (aka Prodigy) teaches a class on Krakoan diaspora at fictional Empire State University (Lanzing et al. 2024, 10).

Works Cited

Ackerman, Spencer. 2018. “How a Podcast Came to Lead the Mutant Resistance.” The Daily Beast, June 2. https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-a-podcast-came-to-lead-the-mutant-resistance/

Barenblat, Rachel. 2018. “Is Ranting Against Globalism Anti Semitic?” The Forward, October 24. https://forward.com/community/412627/globalism-anti-semitism/

Carter, Philip M. 2022. “Long Before Shots Were Fired, a Linguistic Power Struggle Was Playing Out in Ukraine.” The Conversation, March 9. https://theconversation.com/long-before-shots-were-fired-a-linguistic-power-struggle-was-playing-out-in-ukraine-178247

Chambers, J.K., and Peter Trudgill. 1998. Dialectology. Cambridge University Press.

Elbein, Asher. 2024. “The Judgment of Magneto.” Defector, April 24. https://defector.com/the-judgment-of-magneto

Irvine, Judith T, and Susan Gal. 2000. “Language Ideology and Linguistic Differentiation.” In Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Polities, and Identities, edited by Paul V Kroskrity, 35–83. School of American Research.

Goldsmith, Connor. 2020. “Episode 016: Erik Magnus Lehnsherr (featuring Spencer Ackerman).” Cerebro, December 19. 02:58:25. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/episode-016-erik-magnus-lehnsherr-feat-spencer-ackerman/id1529617900

Hickman, Jonathan, Pepe Larraz, Marte Gracia, and Clayton Cowles. 2019a. House of X #1, July 24. Marvel Comics. https://www.marvel.com/comics/issue/72984/house_of_x_2019_1

———. 2019b. House of X #3, August 28. Marvel Comics. https://www.marvel.com/comics/issue/72986/house_of_x_2019_3

Hickman, Jonathan, R. B. Silva, Marte Gracia, and Clayton Cowles. 2019c. Powers of X #4, September 11. Marvel Comics. https://www.marvel.com/comics/issue/72994/powers_of_x_2019_4

Karlander, David. 2025. “The Art and Politics of Micronational Language Planning.” Language & Communication 104: 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2025.06.003

Lanzing, Jackson, Colin Kelly, Francesco Mortarino, Raúl Angulo, and Joe Sabino. 2024. NYX #1, July 24. Marvel Comics. https://www.marvel.com/comics/issue/115475/nyx_2024_1

Lillis, Joanna. 2017. “Kazakhstan: Memories of the Chechen Exodus Don’t Fade.” Eurasianet, February 23. https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-memories-of-the-chechen-exodus-dont-fade

Schweid, Eliezer. 1984. “The Rejection of the Diaspora in Zionist Thought: Two Approaches.” Studies in Zionism 5 (1): 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13531048408575854.

Waite, Sean. 2020. “Assessing Soviet Nationality Policy: a state vested with the power to define, build and destroy nations.” British Online Archives, August 18. https://britishonlinearchives.com/posts/category/articles/377/assessing-soviet-nationality-policy-a-state-vested-with-the-power-to-define-build-and-destroy-nations

Williams, Leah, David Baldeon, Israel Silva, and Joe Caramagna. 2020. X-Factor #3, September 9. Marvel Comics. https://www.marvel.com/comics/issue/78748/x-factor_2020_3