https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262547093/the-unnaming-of-kroeber-hall/

Carolina Rodriguez Alzza: The book The Unnaming of Kroeber Hall states that its focus is not on whether Kroeber Hall should have been unnamed or not. Referring to Yurok chief Robert Spott’s words quoted in the book, “Every story should have a foundation,” what is the foundation for writing a book about Alfred Kroeber’s work and advocacy for Native Californian people and the request to unname a hall bearing his name? Specifically, what key themes or events does the book explore to build this foundation?

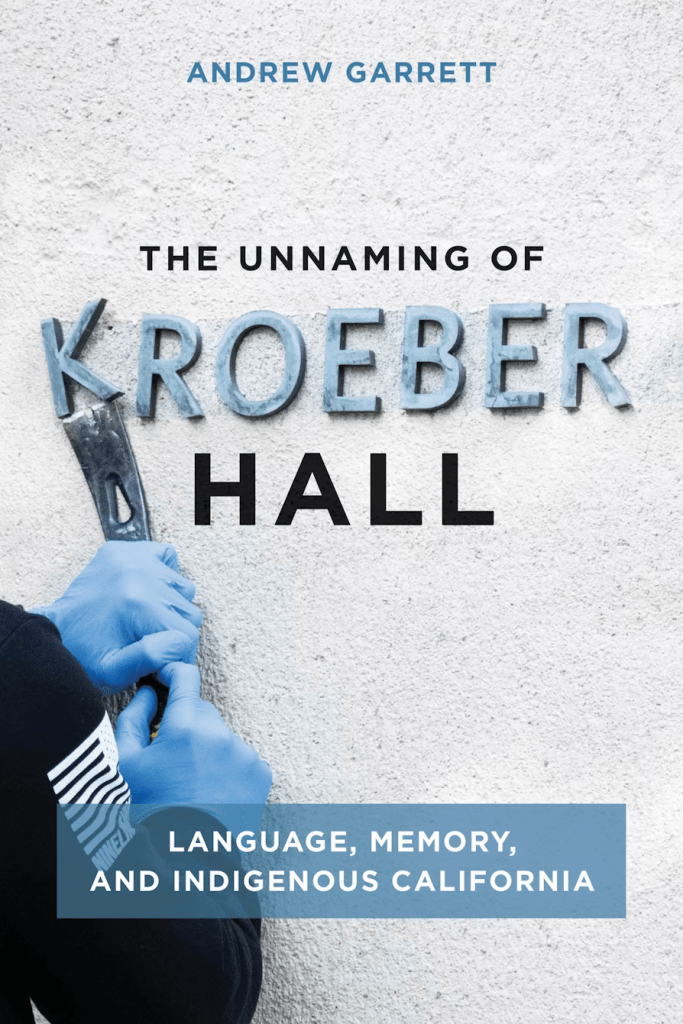

Andrew Garrett: The University of California’s unnaming of Kroeber Hall in January 2021 provides the book’s frame (and, of course, its title), but mainly it is about what Kroeber’s most important work was and how to assess his twenty-first-century legacy. He was exceptionally prolific (with over 500 publications), but I argue that it is not Kroeber’s theories of culture, culture areas, or culture change or other general theories in anthropology that are his main legacy today, but rather the records that he created (and sometimes but not always published) in collaboration with Indigenous people who wanted to document their languages and stories. In The Unnaming of Kroeber Hall, my main goal was to make visible the language and text documentation done by Kroeber and those in his circle, especially including the many Native people whose work he supported.

When Kroeber’s Yurok friend and collaborator Robert Spott said that “every story should have a foundation,” he was referring to one genre of Yurok story: the chpeyuer’ or creation story (another translation is myth), which explains how and why the world is as it is, based on what happened in specific places during the era of creation. The landscape itself is explained by events from the creation time, as are the behaviors of animals, birds, and fish, the appearance of animals and plants, and the practices of humans. Yurok creation stories are anchored in the specific places on the land where the events they record happened. Without such an anchor or foundation, Spott said, a story is an ’er’gerp, literally a telling or tale.

I quoted Spott for two reasons. The first and more important was to emphasize the link between places and stories, between land and culture, for Yurok people and indeed throughout Indigenous California. The second reason was to show that much of what was said in public about Kroeber during the unnaming fracas of 2020-21, including much that was said by university leaders, was unanchored or unfounded. In my book, I returned to the various documents (correspondence, notes, photos) that Kroeber and his colleagues and students created in the first decades of the twentieth century, in order to understand better what their goals were and what they accomplished (and failed to accomplish).

Carolina Rodriguez Alzza: You describe Kroeber’s language documentation legacy on Native Californian languages in detail, emphasizing his personal engagement with Native American people and their mutual appreciation. How does Kroeber’s engagement with Native Californians deepen our understanding of his language documentation legacy and its potential impact on language revitalization efforts?

Andrew Garrett: I stress in the book’s concluding chapter that Kroeber himself did not appreciate how the language documentation that he helped create would be used. He held on to a humanistic (and, as such, perhaps old-fashioned) conviction that people broadly benefit from the intellectual, artistic, and literary heritage of all cultures; he seems for this reason to have been dedicated to recording stories and the languages that encode them. This humanistic perspective is of course extractive insofar as the beneficiaries of Indigenous cultural knowledge are outsiders. But what Kroeber did not realize was that after his death, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Indigenous people throughout California would use these records to relearn languages, retell stories, and reconnect with families and communities.

One important critique of Kroeber, Boas, and others who engaged in research in the same mode is that they were interested only in what they viewed as traditional expressions of culture: they ignored or in some cases even suppressed evidence of adaptation to Euro-American society, cultural hybridization, and the like. This critique is valid (and I add evidence of Kroeber’s own suppression of linguistic hybridization or compromise). But a focus on presumed authentic Native cultural expressions sometimes also now suits puristic ideologies in Indigenous cultural reclamation. In some contexts, that is, what activists seek to recover are precisely the words and stories around “traditional” ceremonies, songs, and the like. Thus Kroeber’s own bias sometimes inadvertently suits today’s needs.

But I also show in the book that Kroeber’s overall project included documentation created entirely by Indigenous people based on their own wishes. One example of several I discuss: Kroeber taught his friend and colleague Juan Dolores, an important Tohono O’odham intellectual, to write in his language and supported his work over many years to create the first extensive corpus of written literature in the O’odham language (amounting to thousands of manuscript pages), also including sound recordings. I also discuss the Northern Paiute language work of Gilbert Natches, similarly supported by Kroeber, as well as community-centered documentation programs he organized in several parts of California.

Carolina Rodriguez Alzza: In the book, it is suggested that Kroeber, whether consciously or not, acted as an intermediary. People shared stories in their languages with him, trusting that he would preserve them for future generations. To what extent was this role predetermined, and to what extent did it emerge through his interactions with these communities?

Andrew Garrett: I think this role was very much emergent; in some ways, it is still emerging six decades after his death. In my book, I cite an anecdote told in 2000 by one of Kroeber’s students that seems revealing about the whole Boasian project as it was implemented by “the first Boasian” (to use Ira Jacknis’s term for Kroeber). George Foster reports that when he was working with Yuki in the 1930s, elder Eben Tillotsen told him, “I want you to make sure you get this right because my children and grandchildren are going to know about this only if they read what you write.” Foster then added, “I thought he had a very far-reaching view of the role of the anthropologist.” I think this dynamic, where an Indigenous participant understood what was at stake in language documentation and what is now often called “salvage ethnography” and the anthropological outsider didn’t appreciate this, was probably typical. Kroeber, like Foster, would have had no sense that the greatest beneficiaries of his work would be Indigenous communities and families themselves.

Carolina Rodriguez Alzza: Chapter 7 is entirely dedicated to Ishi’s experiences immediately before and after he arrived at the University of California’s anthropology museum. How does the provided evidence show Ishi’s choices and shed light on our understanding of his life story?

Andrew Garrett: Ishi’s choices were constrained by many factors; a common narrative is that he was like a “prisoner” or “indentured servant” living in the museum. In chapter 7, I was interested in trying to understand Ishi’s agency — difficult as this is made by the fact that all records of his experiences are from those around him. But these records are from numerous sources, from the anthropologists and linguists who worked with him professionally (whether as his colleagues in the museum or in other, more paternalistic or extractive roles) to the many friends in San Francisco with whom he regularly socialized in the city or on weekend outings, and certain commonalities emerge. One throughline, I argue, has to do with his interest in articulating cultural values through narratives and other pedagogical practices. It can be hard for us now to see this in retrospect, but Ishi’s “academic” work with university researchers was actually of a piece with his “social” work with youths and other friends who were drawn to him and whom he taught about the world.

Carolina Rodriguez Alzza: Finally, why is describing the Kroeber era’s blind spots in the book relevant for a deeper understanding of the decision to unname Kroeber Hall?

Andrew Garrett: As I show in the book, some of the blind spots or unexamined presuppositions of “salvage anthropology” and linguistics (as they are now often called) contributed both to the need to unname Kroeber Hall and to the documentary resources that many Indigenous communities rely on every day. For example, the vanishment assumption that prevailed in U.S. public discourse in the first decades of the 20th century — the idea that Indigenous communities, their cultures, and their languages were on the verge of extinction — motivated collaborations by Kroeber and his students with Native people throughout California (and beyond). These collaborations created archival resources that are now in constant use for cultural and linguistic renewal. But the same vanishment assumption also led to a sense of Indigenous invisibility in public spaces such as universities. As the most prominent early anthropologist working with California’s Indigenous people, Kroeber himself became a symbol of such perceptions and of their many negative consequences. The decision to unname Kroeber Hall was made to ameliorate that symbolic impact.