It was late winter of 2020. I stood near the entrance of a residential building in Oran, Algeria’s second-largest city. I snapped a picture of a spray-painted message: Danger, crumbling building. The scene was not particularly remarkable; Oran is brimming with such “visual noise,”[1] graffiti displaying on external walls the housing dramas taking place behind closed doors.

Seconds later, a man stepped out of a taxicab. He asked me and my companions: Would you like to go inside? We entered the dangerously dilapidated building. The inhabitants ensured I recorded everything: official documents, a decaying roof, floor holes, black mold. Are we not Algerians too? they asked. I had been scripted into their performance of hogra (contempt, disdain, degradation, lowering)—a key Algerian genre of grievance. The state was its ultimate audience; I was merely an instrument for amplifying their case for public housing in the…

“…fight for a piece of the ‘patrimonial cake’ (le gateau patrimonial)[2] of which the state has claimed the lion’s share.”

I contextualize such struggles over urban space on page 99 of my dissertation—Streets of Grievance: Everyday Poetics and Postcolonial Politics in Urban Algeria. They are residues of 132 years of French settler colonialism and stunted postcolonial attempts to repair that past. After independence in 1962, this building was a bien vacant (“an abandoned good”)—property left behind by nearly one million French Algerian settlers (pieds noirs) who fled Algeria after a bloody eight-year war (1954-1962). Postcolonial urban politics have since revolved around the fight for postwar “spoils”—the patrimonial cake increasingly consumed by a few.

My dissertation outlines how ordinary Oranis navigate this political terrain through everyday urban poetics. City dwellers draw attention to everyday life’s forms—both linguistic (placenames, jokes, and strategic code-switches) and urban (the shape of public spaces, traffic lights, and monuments). The confluence of linguistic and urban materiality produces widely circulating sentiments carrying political potential. In the ruins of their beloved city, Oranis reanimate the colonial past in their fight for the patrimonial cake. For example:

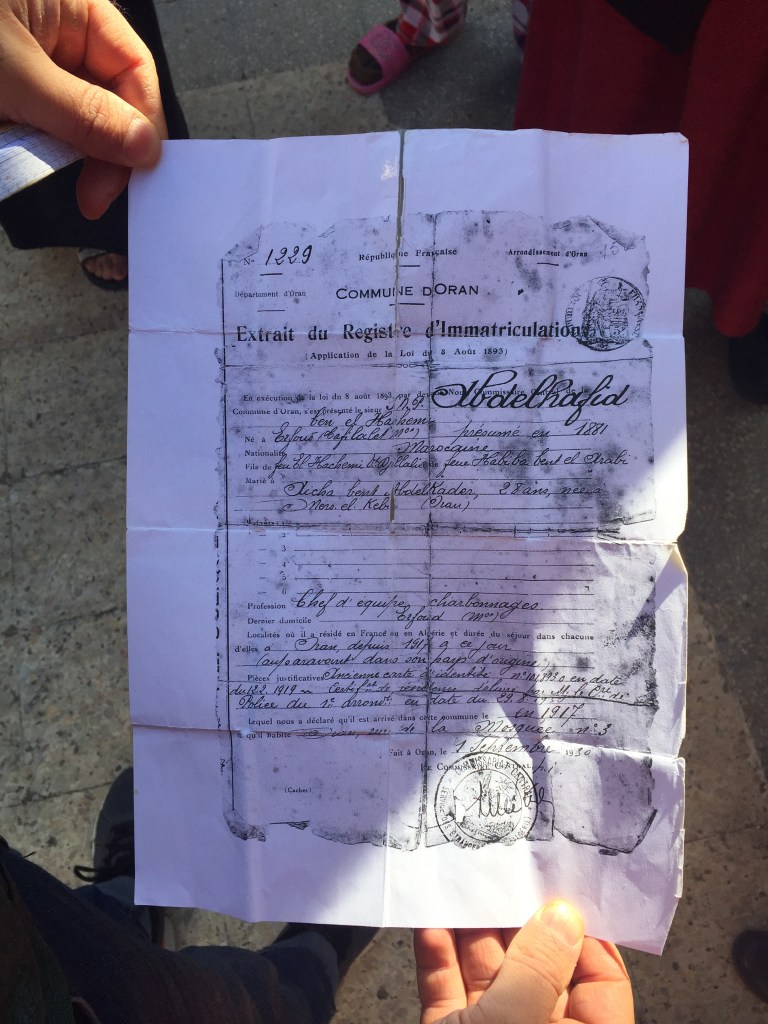

A man holds a photocopy of a French identity card from the colonial era. He uses its mediality to prove his family had been in a decayed building for nearly a century—photo by author.

City authorities have razed historic neighborhoods. In the rubble, former inhabitants post makeshift signs claiming it as private property since the colonial-era—photo by author.

[1] Strassler, Karen. 2020. Demanding Images: Democracy, Mediation, and the Image-Event in Indonesia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

[2] Madani, Safar Zitoun. 2012. “Le logement en Algérie: programmes, enjeux et tensions.” Confluences Méditerranée 2: 133-152.