By Susan Seizer

“In the Western imagination, India conjures up everything from saris and spices to turbans and temples—and the pulsating energy of Bollywood movies. But in America, India’s contributions stretch far beyond these stereotypes. […] Today, one out of every 100 Americans, from Silicon Valley to Smalltown, USA, traces his or her roots to India.”– SITES exhibit website

This post recognizes and recounts a minor victory. It is a victory over the exclusion of Muslims from U.S. representations of who lives in India today and calls it home. The larger issue is one of the misrepresentation of world history in the U.S. by one of our premier national institutions, the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. It therefore concerns all of us, especially those of us who live in academia: it affects both what we learn and what we teach. Though quite small in relation to the work still needed to counter the exclusion and misrepresentation of Muslim lives occurring throughout America today, I record this minor victory here in the spirit of reporting, registering and recognizing every small step we take, in whatever ways we can wherever we live, to further the goal of fostering greater cross-cultural understanding through more inclusive world histories.

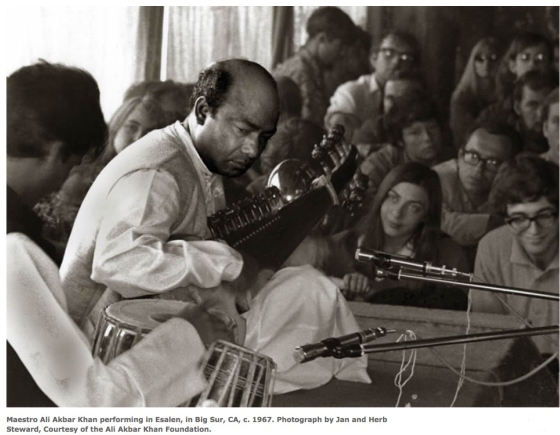

My story begins at the Mathers Museum of World Cultures on the Indiana University campus in Bloomington, IN. This semester, Spring 2016, the Mathers Museum is hosting a traveling exhibit on loan from the Smithsonian. The traveling exhibit is entitled Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation.

In its first and fullest incarnation, the exhibit ran at the Natural History Museum of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. for over a year, from February 27, 2014 – August 16, 2015. There, it included photographs, artifacts, videos, and interactive stations designed to allow visitors to “learn about the Indian American experience and their dynamic role in shaping American society.” The exhibit “explores the ‘American Dream’ as lived by Indian Americans.”

The traveling exhibit is a smaller affair but its gestalt is the same. Without artifacts, videos, or interactive stations, the traveling exhibit is comprised of twenty-four wall-hung panels with text, photographs, charts and graphics, as well as mounted thalis (plates). On tour through January 2019, it travels to museums, galleries, and history centers across the U.S. in ten-week periods. Its stop at the Mathers Museum is the midpoint of a tour that, so far, comprises eight venues and stretches from California to South Carolina.

| Opening – Closing | Host Institution | Status | |

| 05/02/2015—07/12/2015 | Morris Museum, Morristown, NJ | Booked | |

| 08/01/2015—10/11/2015 | Olive Hyde Art Gallery, Fremont, CA |

Booked | |

| 11/08/2015—01/10/2016 | Sonoma County Museum, Santa Rosa, CA |

Booked | |

| 01/30/2016—04/10/2016 | Mathers Museum of World Cultures, Bloomington, IN | Booked | |

| 04/30/2016—07/10/2016 | Minnesota History Center St. Paul, MN |

Booked | |

| 07/30/2016—10/09/2016 | John E. Conner Museum, Texas A&M University, Kingsville, TX | Booked | |

| 10/29/2016—01/08/2017 | City of Raleigh Museum, Raleigh, NC |

Booked | |

| 01/28/2017—04/09/2017 | City of Raleigh Museum, Raleigh, NC |

Booked | |

| 04/29/2017—07/09/2017 | South Carolina State Museum, Columbia, SC | Booked | |

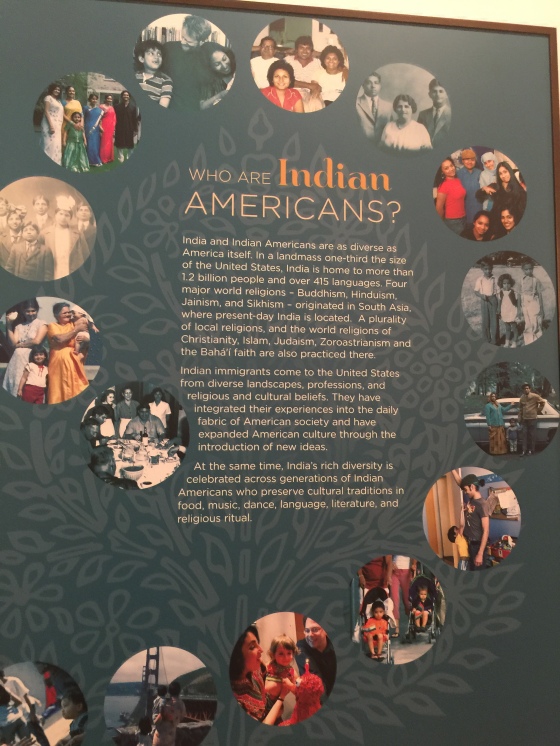

When I first encountered the exhibit, one of its introductory panels was entitled “Who are Indian Americans?” The first paragraph of the panel however was not about Indian Americans at all, but rather about India – its landmass, its population, its linguistic breadth, and its religious makeup. That first paragraph read:

“India and Indian Americans are as diverse as America itself. In a landmass one-third the size of the United States, India is home to more than 1.2 billion people and 415 languages. It is also home to four major world religions – Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism.”

I read this prominently placed text on the opening night of the exhibition at the Mathers Museum during a rather gala ceremony. The event included proud speeches by a University Provost and the Museum Director; a lovely live vocal performance of Carnatic music by Lavanya Narayanan, a south Indian undergrad; and a delicious catered spread of Indian snacks. The mood was celebratory and the exhibit’s opening had been much anticipated. The crowd was thick and I did not make it into the actual exhibit hall to peruse and read the exhibit panels until the excitement of the opening event had died down a bit. When I did, I felt a creeping disbelief: Am I really seeing this? Does this panel really MAKE NO MENTION OF ISLAM? I continued to wander through the exhibit, noting a panel recognizing Sikh taxi-drivers, another naming the first Indian American astronaut, the first Indian American to earn a Nobel Prize, an award-winning Indian American gymnast and the first Indian American comedian to have her own TV show (Mindy Kaling). There were many notable others. But I kept circling back to that first panel about India and its religions and trying desperately to understand how it was possible that this show — an exhibit that had been up at the Smithsonian for over a year and traveled for the next half year to several cities in the U.S. before I was seeing it in Bloomington — mentioned India as home to only four religions, and these did not include Islam.

I read this prominently placed text on the opening night of the exhibition at the Mathers Museum during a rather gala ceremony. The event included proud speeches by a University Provost and the Museum Director; a lovely live vocal performance of Carnatic music by Lavanya Narayanan, a south Indian undergrad; and a delicious catered spread of Indian snacks. The mood was celebratory and the exhibit’s opening had been much anticipated. The crowd was thick and I did not make it into the actual exhibit hall to peruse and read the exhibit panels until the excitement of the opening event had died down a bit. When I did, I felt a creeping disbelief: Am I really seeing this? Does this panel really MAKE NO MENTION OF ISLAM? I continued to wander through the exhibit, noting a panel recognizing Sikh taxi-drivers, another naming the first Indian American astronaut, the first Indian American to earn a Nobel Prize, an award-winning Indian American gymnast and the first Indian American comedian to have her own TV show (Mindy Kaling). There were many notable others. But I kept circling back to that first panel about India and its religions and trying desperately to understand how it was possible that this show — an exhibit that had been up at the Smithsonian for over a year and traveled for the next half year to several cities in the U.S. before I was seeing it in Bloomington — mentioned India as home to only four religions, and these did not include Islam.

I was no doubt particularly sensitized to this omission for two reasons. For one, I had just finished teaching four weeks of Indian history to undergrads in the Anthropology Department at IU. I had introduced students to the back and forth dominance of Islamic and Hindu rulers in the subcontinent now known as India since 711 CE (Wolpert 1982). These were the first four weeks of a course on South Asian diasporic filmmakers in which, to prepare students for the diasporic films we would screen over the course of the semester, in these first weeks we had also watched two films that represented something of the more recent fraught relations between the Hindu and Muslim communities in India, Satyajit Ray’s “The Home and the World“ and Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi”. They would shortly watch Deepa Mehta’s film “Earth”, an extremely powerful rendering of Bapsi Sidwa’s 1988 autobiographical novel Cracking India that chronicles the extreme violence of Partition. I had encouraged the students to visit the Beyond Bollywood exhibit the timing of which dovetailed so perfectly with the course. How confused would they be, I wondered, to read this “Who are Indian Americans?” panel that makes no mention of the presence of Islam in India?

The following week I told my students about the exhibit. They questioned how relations so central to the birth of the Indian nation could just be erased. We talked about the difficulties inherent in representing history. Students were angry that what they might learn of India in a top national museum could mislead them to this extent. I started asking other people who’d seen the exhibit whether they had been struck by this omission. A Muslim grad student who had come to the States to study only this year admitted that she had felt alienated on reading this panel. A Muslim colleague on the faculty told me, “Yeah, I noticed it. But I guess it just seemed par for the course.” Par for what course, exactly? Not mine; and no course with which I want to be associated. Nor did I want more people to feel this way.

Which brings me to the second reason I was sensitized, and why I imagine others too might bristle, as I did, at any representation that erases from history an entire Muslim population at this particular moment: the course of the current presidential election season in the U.S. The Governor of Indiana has closed our state to Muslim refugees. The front runners of the Republican party want to see all Muslims kicked out of the U.S. Globally, the very people most at risk for their lives are scapegoated, turned away and sent back to the places where the violence they fled still reigns.

It took little time for a coalition of faculty and students at IU to agree to sign a letter I wrote to the Director of traveling exhibits at the Smithsonian. The letter politely requested that the text of the “Who are Indian Americans?” panel be changed. It reads in part:

We are a group of students and faculty who study, teach, research, and write about the history and culture of South Asia and the South Asian diaspora. It is exciting to see a Smithsonian exhibit that attempts to capture multiple facets of the Indian American experience while introducing this diasporic community to museum goers across the country. Thank you for taking on this challenging educational mission!

Of the many informative panels in the SITES exhibition however there is one particular panel that has stunned and alienated those of us who are students and embarrassed those of us who teach course on the history and culture of India. This panel seems to misrepresent Indian history and to exclude whole populations in present day India. This is the panel entitled, “Who are Indian Americans?”

We want to draw your attention to what we feel is the unacceptable omission of Islam and Christianity from this reckoning of the people and languages of India. […]

After Hinduism, which comprises 80% of India’s population, and Islam, 14.8%, the third largest minority religious community in India are Christians, accounting for 2.3% of India’s population. Only then come the Sikh (1.8%), Buddhist (0.8%), and Jain (0.4%) populations listed in the SITES panel. Rather than getting into a numbers face-off here, however, we would instead like to see the panel include recognition of India as also home to Islam, Christianity, and other tribal and minority religions.

It may be that the primary problem with the panel’s perceived omission is a semantic one that turns on the different possible definitional interpretations of the word “home.” If by “home” the panel means to signify that these four religions originated in India, the text would do well to clarify this point (however as there are also numerous tribal religions that originate in India, using this definition renders problematic their omission).

We feel that the most common interpretation of the word “home” is one that understands this word as referring to in the place that people who dwell there regard as their home.

So what might we like to see done at this juncture? Given that the SITES “Beyond Bollywood” exhibit is already up at the Mathers Museum, we would like to request your permission, in your capacity as Director of SITES, to rectify this omission in some way. We are open to your suggestions about how to do this.

The full letter to Director Springuel

Our polite letter was met an equally polite and productive response. It read:

From: Myriam Springuel

Date: Monday, February 22, 2016 at 4:30 PM

Subject: Re: Collective concern over one panel in SITES “Beyond Bollywood” exhibit

Dear Dr. Seizer:

Thank you for your comments on Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation. We at the Smithsonian take seriously our mission—the increase and diffusion of knowledge—and we want to ensure that no part of our work is inaccurate or subject to misinterpretation. We are talking with the curators who developed the exhibition and will get back to you shortly on our next steps to address issues raised in your letter.

Thank you very much for sending a thoughtful letter. Please let your colleagues and students know that we take comments such as these seriously and will be back to you shortly with a solution.

Myriam Springuel, Director

Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES)

Director Springuel met with the exhibition curators, and in a spirit of good will and understanding they decided to produce a replacement panel. Her email one week later read:

Dear Dr. Seizer:

I have conferred with my colleagues here at the Smithsonian and we are in the process of updating the language on the Beyond Bollywood exhibition panel as follows:

“India and Indian Americans are as diverse as America itself. In a landmass one-third the size of the United States, India is home to more than 1.2 billion people and over 415 languages. Four major World religions – Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism – originated in South Asia, where present-day India is located. A plurality of local religions, and the world religions of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Zoroastrianism and the Bahá’í faith are also practiced there.”

As soon as the panel updates are complete, they will replace those in the current exhibition.

Again, thank you for your comments that raised this to our attention.

Myriam Springuel

What a gratifying exchange! One student’s response: “Well, it’s not perfect, but at least it’s not wrong.”

References:

Wolpert, Stanley. 1982. A New History of India. 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Susan Seizer is an anthropologist at Indiana University. She has conducted ethnographic fieldwork in South India and the US. She writes mostly about live performance, humor in use, and social stigma. Seizer is the current editor of the Camp Anthropology blog.

Wonderful! Shows how you can challenge “the system” in a constructive way and change it.

LikeLike